Trees of Significance: How Non-Native Trees Create a Sense of Place Away from Home

Trees are the point of connection for everyone who works with the Tacoma Tree Foundation. We share a love of trees and the conviction that they make Tacoma's communities resilient in the face of climate change. In addition, our understanding of how trees matter—scientifically, culturally, and emotionally—is shaped by the unique relationships each member of TTF has to trees. This is why we decided to develop "Trees of Significance," a series of blog posts where staff, volunteers, and partners share how they connect to trees in response to the following questions: How do trees connect us to place? How do they connect us to what we do? What is our emotional and embodied relationship to trees? Each post will include printable Tree ID guides.

For our very first post in the series, Eden Standley interviewed Director of Partnerships and Communications, Adela Ramos.

“Trees are a point of connection and gathering,” says our Director of Partnerships and Communications, Adela Ramos, and it is not just in the work of their root systems that trees create connections. Trees shape our sense of place, as I explored in this blog post about how trees and their absence reveal the historical value assigned to specific neighborhoods and communities, and how this impacts our experience of where we live, work, and walk. In addition, trees also shape our sense of place by reminding us of elsewhere; this might be especially true for non-native trees which abound in today’s urban forests.

Learning about non-native trees teaches us about cross-cultural relationships that connect places and peoples across the globe. They remind us that planting a tree can be an expression of admiration for a loved one or an entire culture, as well as a way to welcome others into our cities.

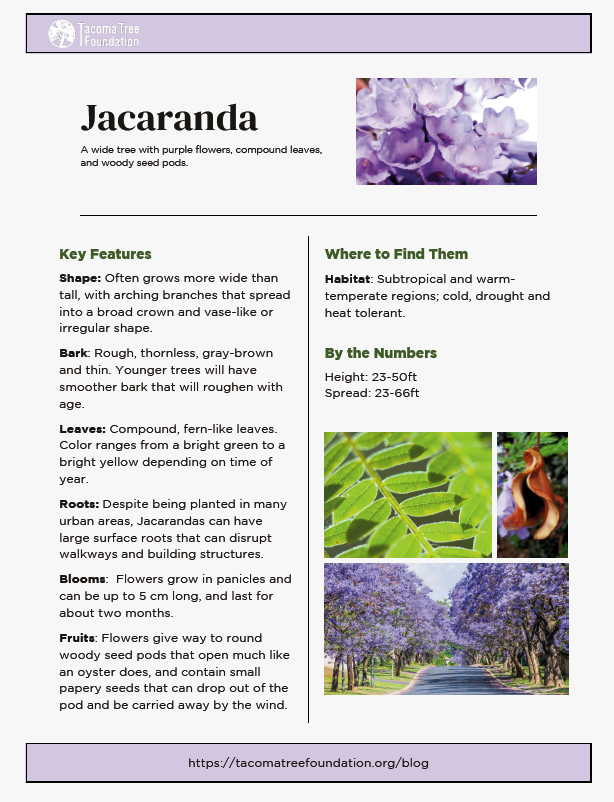

Adela and I got together one gray December morning to talk about how non-native trees connect her to place. She grew up in Mexico City and has lived in Tacoma for 13 years. Two trees that have become especially significant for her after living in each of these cities are the Japanese Yoshino Cherry, which is native to Japan but grows in Tacoma and across the United States, and the jacaranda (ha·ka·rán·da), which is native to South America, but grows in Mexico City. It is important to note that non-native species are not invasive species. The former are introduced via human activities (e.g., importing plants), adapt to their new environment without causing harm, and even provide environmental benefits, whereas the latter can threaten ecological stability. Some experts argue that the main difference really comes down to the relative harm caused, since some invasive species can become adaptive and in time benefit the environment (e.g., ivy).

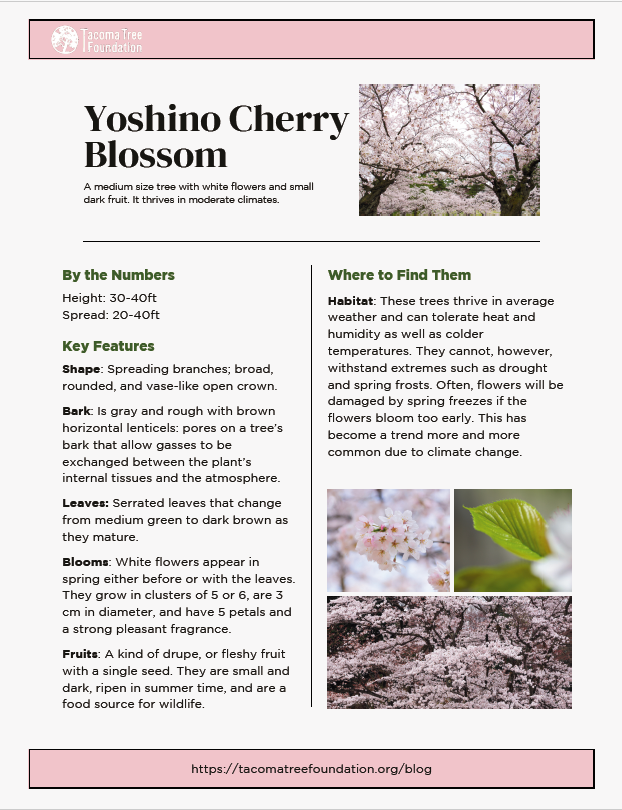

The cherry blossom and the jacaranda were each introduced to their current environment through a surprisingly similar history of cross-cultural relationships. At the heart of this relationship is their shared characteristic—beautiful blooming flowers. While the trees differ in size, both produce bright ornamental flower displays in spring, are popular in urban areas for beautification, and, in the case of the U.S. and Mexico City, “were each introduced by way of relationships with Japan,” Adela adds.

Cherry blossoms came to the U.S. in 1912, as a gift from Mayor of Tokyo, Yukio Ozaki, to celebrate the growing diplomatic friendship between the U.S. and Japan. In return, President Taft sent a shipment of flowering dogwoods.

The cherry blossoms were first planted in Washington, D.C., between 1912–1920 in the public parks around the White House, and over time spread to more cities in the U.S.

Yoshino cherry blossoms. Photo Credit: Eden Standley.

In 1930, the President of Mexico, Pascual Ortiz Rubio, visited the white house and, upon witnessing thousands of blooming cherry blossoms, decided he wanted the same for Mexico City. However, the city’s temperate climate was not cold enough to stimulate the cherry blossom’s winter dormancy, which is critical for them to bloom. The Japanese Ministry of Foreign affairs recommended he consult with Tatsugoro Matsumoto, a Japanese landscape architect and recent immigrant to Mexico City. Matsumoto recommended the jacaranda. Soon, Mexico City’s streets were bursting with the grand blue-purple flowers that still canopy its busy avenues.

“It was living in Tacoma that I realized how important the jacaranda was for me because the city where I had lived before coming here, and after moving away from Mexico City, had a very short spring,” Adela recounted.

Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Spring occurs in both Mexico City and Tacoma from mid-March to early June, but the average high temperature in Mexico City only rises 3 degrees in March and remains at a stable 75 until June. While in Tacoma the average high temperature rises 5 degrees in March, and then another 15 degrees in June. “I was actually aware of the pace of spring for the first time probably in my life... In Mexico City, we have year round blooming plants, and so flowers remind us of the month we are in and what fruits are available in the market, not so much of sharp seasonal transitions.”

A typical spring scene in Mexico City’s streets during the height of jacaranda blooming. Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In both Tacoma and Mexico City, cherry trees and jacarandas produce huge flower displays around the beginning of springtime. For Adela, “a blooming tree can transform a street in a city where there’s concrete and hard sidewalk and traffic, and for me it’s the power of how a blooming tree can soften everything around it, and how it softens us after the harsh winter… it helps you get back into that part of who you are and what you need.” These blooming trees both beautify our cityscapes and keep the rhythm of the seasons, and through doing so they help us to stay mindful. “When you are under a cherry blossom tree and it’s in full bloom, you just feel completely transported, like there is light shining on you, a certain kind of warmth, wonder. I had only felt that under a jacaranda in March, which is when they bloom.”

Under the canopy of a tree is a great place to engage in mindfulness, which is the practice of being aware of one’s internal states and surroundings. Recent studies have shown that mindfulness practices can reduce anxiety and depression, help people coping with stress or serious illness, and cultivate a sense of contentment in life, among other things. Mindfulness might be an important part of living a long and healthy life.

I got the feeling that the mindfulness Adela has about the blossoming of trees is also important for her sense of belonging to a place. Her descriptions of it remind me of the ancient Japanese practice of hanami, literally “flower viewing.” When the cherry blossoms were brought to the United States, hanami followed. Cherry blossom festivals are still held around the country, there are even a few in Seattle.

Toyohara Chikanobu (1894), Ladies in the Edo palace enjoying cherry blossoms. Image Source. Wikimedia Commons.

Adela’s connection to the jacaranda via the cherry blossom might also be understood in relation to historian Dr. Mario Sifuentez’s work on how immigrants create a home in the landscape of the Pacific Northwest. In the fall 2023 webinar he offered for TTF, Sifuentez discussed how tree planting, especially of culturally significant plants, can give people who move from place to place a sense of belonging, a topic he studies in Of Forests and Fields. Sifuentez explained: "specifically when we're talking about immigrants or migrants, [the] way of belonging actually becomes a way of behaving because belonging suggests permanence... behaving actually gives them more of a sense of something that they can take with them.”

We all have behaviors that make us feel we belong to a place, rituals or behavior patterns that are place-specific. Some examples that Dr. Sifuentez offered in relation to Mexican immigration, were the establishment of tortillerías (tortilla shop), Spanish-language radio stations, or cultivating culturally significant foods or plants. Dr. Sifuentez pointed out that, especially in the U.S., "the way that the work [of tree planting] is rooted in histories of exclusion and histories of racism and redlining, it becomes incredibly important to create spaces that are livable and welcoming, that improve quality of life for communities of color and immigrant communities."

Engage in a little virtual hanami to keep you going as we reach the beginning of blooming season: watch late spring Kwanzan cherry blooms move with the wind and travel through a Tacoma neighborhood street last year in this personal video taken by Adela.

Culturally significant trees in particular can make the places where they are planted more welcoming and hospitable to new residents.

As they were when first brought to the U.S. and Mexico, cherry blossoms and jacarandas can be considered trees of cross-cultural admiration. Their histories and current significance can encourage us to be mindful of the relationships between our three cultures, and this includes acknowledging how racism has also shaped US-Japan and US-Mexico relationships. In this light, these trees can be symbols of remembrance, like the five Yoshino cherries planted at the University of Puget Sound’s campus to honor student descendants of the Japanese-Americans who were sent to internment camps during WWII. Entwined in these trees are moments of beauty and moments of rupture.

The Yoshino cherry blossom and jacaranda teach us that we must do our best to cultivate respectful relationships with nature and with each other. We can look to these trees as models for how to make our urban spaces more welcoming to people of other cultures.

We hope you will think of this the next time you see a cherry blossom tree here in Tacoma, or a jacaranda in Mexico City.

Learn how to identify these trees of significance using our printable guides. Click on the corresponding image below to download each guide:

The guides were created by Eden Standley, Outreach Specialist, and Julia Wolf, Communications Specialist.